Lobotomy Cases From the Past Continue to Educate, Spark Interest

In November 1948, a “psychosurgical showdown” of sorts drew a crowd of the most esteemed neurosurgeons, neurologists and academics to the Institute of Living’s Burlingame Research Building.

In the building’s newly minted psychosurgery suite — the first and only one of its kind at the time — William Scoville, MD, founder of the Hartford Hospital Department of Neurosurgery, and Walter Freeman, MD, each demonstrated their preferred approaches to the lobotomy on four female patients.

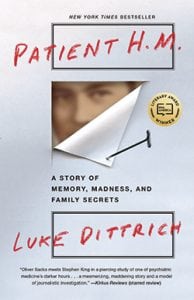

The historical scene, which went on to impact lobotomy technique and eventually modern understanding of memory, was described by Luke Scoville Dittrich to a packed room at the IOL’s weekly Grand Rounds lecture series.

Dittrich, the grandson of William Scoville, is a contributing writer for the New York Times Magazine and author of “Patient H.M.”, from which he shared excerpts during his presentation.

They included a famous 1953 case that has since become the most widely studied in the history of neuroscience. While attempting to surgically cure an epileptic patient named Henry Molaison, Scoville removed his medial temporal lobe. The resulting effect on Molaison was anterograde amnesia, which left him unable to create long-term memories. Although tragic, his case played an important role in the study of memory and brain function.

The modern lobotomy, which was introduced in 1935 and popularized in the 1940s, was a neurosurgical technique that consisted of the cutting or scraping away of a patient’s prefrontal cortex. The intent of the procedure was to treat and reduce the symptoms of mental illness, but often bore serious implications on the patient’s personality and cognitive function.

That day in 1948 at the IOL, Scoville, Dittrich’s grandfather, was the first to perform a lobotomy. His technique, dubbed the “selective cortical undercutting,” offered a cleaner approach to an otherwise sloppy procedure. Using a drill outfit with a one-and-a-half inch trephine bit, Scoville put two precise holes in his patient’s skull – one over each eye socket. From there, he used a suction tip and spatula to remove the fibers connecting the frontal cortex to the rest of the brain, diminishing frontocortical function while maintaining the physical structure.

Freeman was up next. The man considered the “father of the lobotomy,” who would eventually perform up to 25 lobotomies in a day, had created a quicker and more efficient method called the transorbital lobotomy, or “ice-pick lobotomy.”

After rendering the patient unconscious through electroconvulsive shock, Freeman used a thin metal tool that resembled an ice pick to enter the patient’s skull through the eye socket, tapping the pick to break through the thin bone behind the eyes. From there, he would swish around, destroying the fibers of the prefrontal cortex, before removing the pick and repeating the procedure on the other side.

Luke Scoville Dittrich speaks at an IOL Grand Rounds.

The practice of lobotomies was controversial from its inception. The evidence of their risks and negative consequences ultimately outweighed any evidence supporting their utility and it faded from use during the 1950s. However, it’s estimated that almost 40,000 people were lobotomized in the United States during that time.

Scoville’s new method of lobotomy eventually inspired him to explore other regions of the brain, including the medial temporal lobe.